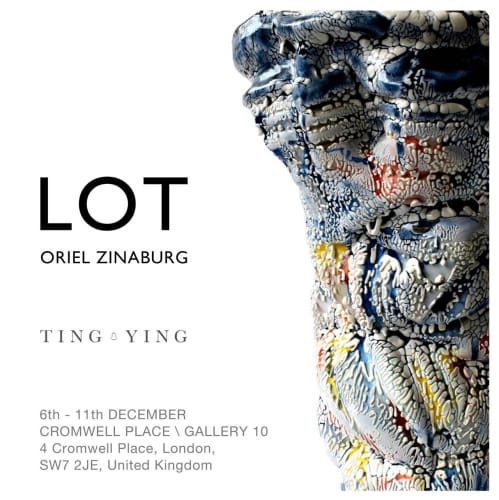

The story of Lot's wife, who was turned to a pillar of salt, when she looked back on burning Sodom and Gomorrah, is a puzzling one. For ceramic artist Oriel Zinaburg, however, it offers an indelible image: of the onward rush of life and the fluidity of emotion stilled in an instant. Combine that with Oriel's love of the Negev desert and his admiration for its complex layered geology, and you can begin to see the origins of his most recent work.

These large-scale sculptural vessels made of marbled clay, spiraling from narrow bases with a centrifugal energy before being dressed in multiple layers of glaze, reflect his fascination with the material and its interaction equally with the elemental forces of nature - fire and water - and the drama of human feeling. Based on press moulded three dimensional images of his own head, at three different ages, these extraordinary, unruly objects grow through an intuitive process of hand-building and collage. Oriel tears, folds and distorts the material, following where the process leads him, guided by instinct, enabling bulges or squeezing in to a neck, until he achieves a sense of resolution. Then he glazes the pieces through multiple firings, surrendering the final outcome to the vagaries of the kiln and the transformations that occur within its fiery interior. The finished work is what the artist calls a frozen moment, still charged with the dynamism of its making but, as if caught unawares, preserved forever.

Born in Israel, Oriel Zinaburg first studied fine art in Jerusalem before winning a scholarship to London's Architectural Association to study architecture. For many years he worked as an architect in the UK, on major developments but also on smaller scale interior projects. In one two week break between jobs, however, in 2015, Oriel took a course in mould-making at Central Saint Martins School of Art. He was hooked. He began to reduce his work hours to fit around his new art practice. He rented studio space. And then lockdown released him to focus entirely on his making.

Oriel's self-taught way of working is grounded in mould-making. To that extent each of these pieces is a self-portrait. But the clay positive bearing his features is transformed through multiple processes into something quite other, with its own vitality, though ultimately expressive of the human activities of thinking, dreaming, and making. Through a period of rapid experimentation, Oriel has grown bolder in his forms and glazes. He draws not just on memories of the desert but of many natural phenomena including the miraculous gogottes, naturally occurring sculptures dating back thirty million years, discovered in Fontainebleau, France. He is also influenced by the surrealism of Salvador Dali, whose objects droop and metamorphose, by Abstract Expressionism and by Pop Art. He is increasingly captivated by the painterly potential of his vessels - their character as three-dimensional canvases - across which he is thrilled to drip, layer and cluster his glazes.

But Oriel is clear that the primary joy of ceramics is its unpredictability. "What you don't have in fine art," he says, "is the element of chance. With clay, you are in control up to a certain degree - but then you have to embrace what happens in the kiln. The material and the process dictate to some extent. That is a huge part of the beauty of the medium for me." Brimming with the zeal of the convert, the choice of title reflects perhaps another intuition: that the story of Lot's wife is also about not looking back. Both as an exile, settled in the United Kingdom, and as someone who has turned his back on architecture to embrace fully his new identity as a potter, Oriel is just looking to the future.

Emma Crichton-Miller

Editor in Chief, The Design Edit